Livestock farmers, who are engaged in a jaguar mitigation project with Ya’axché, are realizing that humans and jaguars can coexist.

Below the foothills of Aguacate village in Toledo, southern Belize, nestles a cattle ranch owned by small scale farmer Abraham Kan. Before sunrise, Kan along with his two dogs sets out on a routine mission to check-up on his cattle. He rallies his cattle with a whistle, and they gather to enjoy the molasses and salt supplement he provides.

One morning in 2014, as Kan gathered his cattle and began doing a headcount, he realized one cow was missing. He followed up with another whistle but it was futile. Kan became worried that his cow was injured and decided to set out in search of it. Near the outer edge of his cattle pasture, in the forested area of his land, his cow lay dead. Due to visible marks and the condition of the body, he strongly believed that a jaguar was responsible for the death of his cow. He set out to track the elusive jaguar but with no success. In the following years, he came across cat tracks but there were no further attacks on his livestock. The experience left him with more questions than answers and made him more determined to find out what led to the death of the cow.

In 2016, Kan responded to an invitation to a workshop organized by Ya’axché to discuss jaguar predation on livestock in Toledo. Kan, along with 22 other livestock farmers, expressed their concern regarding jaguars preying on cattle, sheep, pigs, chickens and dogs. Yahaira Urbina, representative from a conservation partner Panthera/UB-ERI, provided insights on jaguar ecology. Shanelly Carillo, Belize Forest Department’s jaguar officer, raised awareness on the laws protecting jaguars in the small Caribbean country. Ya’axché’s Marchilio Ack and Karla Hernandez-Aguilar shared lessons learned from other countries in the region where farmers were experiencing similar clashes with jaguars. Karla introduced a project to implement mitigation measures and reduce conflict. Kan, being a vocal individual, shared his reluctance and hesitation that some of these measures might address the problems with jaguars.

In 2017, Ya’axché’s human-jaguar conflict team, made up of Marchilio and Karla, visited Kan’s farm and 29 others. They created farm profiles in order to select sites for implementing mitigation measures. Within 2 weeks, 9 farms – including Kan’s – were chosen to be included in the human-jaguar conflict program. Kan and the other farmers pledged their support to work with the team to find solutions to the conflict. As a follow up, Ya’axché’s human-jaguar conflict team identified farm management improvements and locations where camera traps could be deployed.

Soon the mitigation equipment arrived. The sound alarms, solar lights and camera traps were tested and set up in strategic locations on Kan’s farm. He received training on how to monitor and utilize the equipment. As a further improvement to Kan’s farm, a corral was built – a well-illuminated area where his cattle could spend the night. Kan was excited that he might soon see photos of jaguars captured by the camera traps but time passed with no photographic evidence of jaguars.

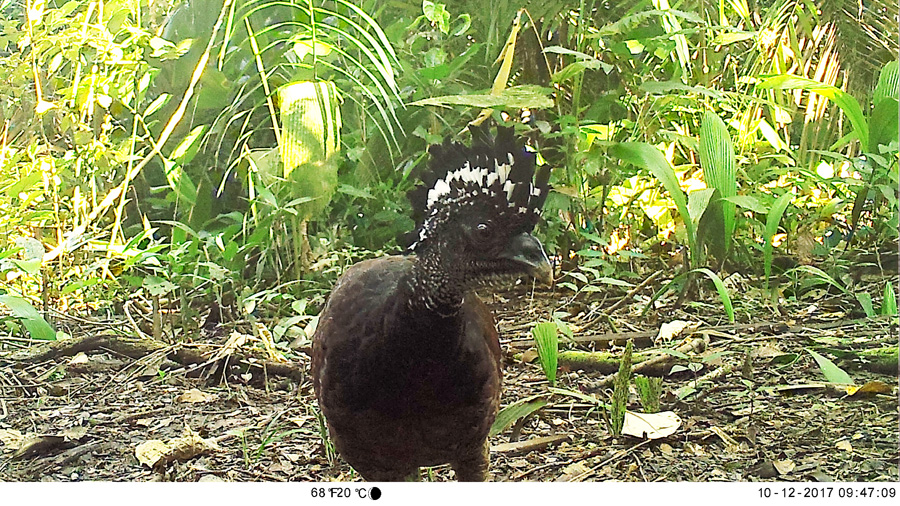

On the first day in November 2017, Kan reached Ya’axché’s Punta Gorda office before opening hours and uttered to Karla as she arrived, “I have something for you to see!” He handed her a memory card and photographs of a jaguar began popping up on the computer screen. He finally had it – confirmation that a jaguar was living on his land! As time lapsed, the camera trap captured amazing photos of other wildlife; especially fascinating was an image of the jaguar coming into frame with an armadillo in its mouth. The memory card contained other unique and difficult to obtain images such as a tapir with her calf and that of a baby jaguarundi watching her mother hunt. Kan’s reaction wasn’t one of fear but of pride in knowing that his land was providing a home for wildlife. He expressed interest in sharing the photos and findings with his community members.

Honoring this incredible request, the human-jaguar conflict team joined Kan at Aguacate village where he had arranged a 30-minute presentation at the primary school. The team was greeted with 60 students who were from 4 different standards (grades). To begin the interactive sessions, the team introduced the human-jaguar conflict project, talked about jaguar ecology and identified the five cats found in Belize – jaguar, puma, ocelot, margay and jaguarundi. Near the end of the session, Kan stepped up to share the photos captured on his farm. “This is from my land!” he proudly asserted as the photos in the presentation slide changed. The students were amazed to see for the first time a jaguar, peccary, ocelot, deer, tapir, coatimundi, tayra, and jaguarundi. Kan was grateful for the opportunity to share that the forested area on his land is a haven for wild animals.

To date, Kan has not lost another cow and has realized that the area of his land which he keeps forested is home to incredible wildlife; moreover, jaguars are coexisting near his cattle pasture. He has committed to keep the area of his land forested as a conservation zone for wildlife to traverse and live. He now has a renewed perspective on jaguars. He understands that when farms are properly managed and there is plenty of food in the forests for Belize’s biggest wild cats to survive, conflict between jaguars and human can be avoided. He continues to promote the importance of coexisting with jaguars among his neighbors in Aguacate village.

Kan continues to take care of the equipment provided to him and is recording information on the mitigation measures adopted. Ya’axché’s human-jaguar conflict team still checks in with him. “This project has opened my eyes. I only saw tracks of animals on my land but now I know what lives in my forest.” remarked Kan.

Ya’axché will continue working with Kan and other livestock farmers in southern Belize as we continue to find solutions to the human-jaguar conflict. More importantly, the successes of Ya’axché’s projects are shared with the public and with members of a jaguar working group which operates in other parts of Belize. This work has been financially supported by the US Fish & Wildlife Service. This work greatly contributes to our successes in protecting wild places and working with communities in southern Belize.

Update September 24 2018: We are currently raising funds to work with 2 additional farmers to create 2 “jaguar friendly” farms. Donate towards our Global Giving campaign to Reduce Clashes Between Jaguars & Farmers in Belize.